Chapter 5: Creating Campaigns

The arrival of a mind flayer nautiloid means trouble for

any world—and adventure for that world’s heroes!

If encounters are the building blocks of a D&D adventure, then adventures are the building blocks of a D&D campaign, for a campaign is what you get when you string two or more adventures together. A campaign setting is the world in which those adventures take place—both a backdrop for your adventures and a hotbed of conflicts and personalities that can inspire and drive adventures.

Step-by-Step Campaigns

Follow these steps to create a campaign:

Step 1: Lay Out the Premise. Consider the core conflicts driving the campaign, and choose a setting that reinforces the themes and tone you hope to evoke.

Step 2: Draw In the Players. Start your campaign in a memorable way. Determine how the characters get drawn into events and how the characters’ goals and ambitions might come into play.

Step 3: Plan Adventures. Consider the smaller conflicts that make up the larger conflicts of the campaign, and devise fun quests that help drive the story. Flesh out the antagonists, the important locations, and the elements that link the adventures together.

Step 4: Bring It to an End. Think about how the campaign might end and what level you expect the characters to be when the campaign wraps up.

You might have noticed that these steps are similar to the “Step-by-Step Adventures” list at the start of chapter 4. In many ways, a campaign is just an adventure writ large. In an ongoing campaign, one adventure flows naturally into the next.

Later sections of this chapter offer inspiration and advice for each of these four steps. The chapter concludes with a campaign example.

Your Campaign Journal

At the start of any campaign, there’s a buzz of excitement as you and your players look forward to creating a new world together—one full of adventure and promise. Every game session is a chance for you to show off more of the campaign setting and deepen your players’ investment in it.

If your campaign lasts for months or years, sustaining that high level of excitement—yours as well as your players’—takes effort. An important tool to help you keep interest in the campaign high is a campaign journal, a collection of notes from past sessions. Use your journal to refresh your memory on events that transpired early in the campaign and bring closure to unresolved conflicts and mysteries.

Keeping a Journal

A campaign journal documents the progression of your campaign, from the first game session to the last. Your journal can take whatever form works best for you. It might be a physical notebook; a binder of loose notes, maps, and tracking sheets; a wiki; or a collection of files on your computer. Journal entries are best organized by date or game session. (Some DMs prefer the term “episode” to “game session,” but the terms are interchangeable.)

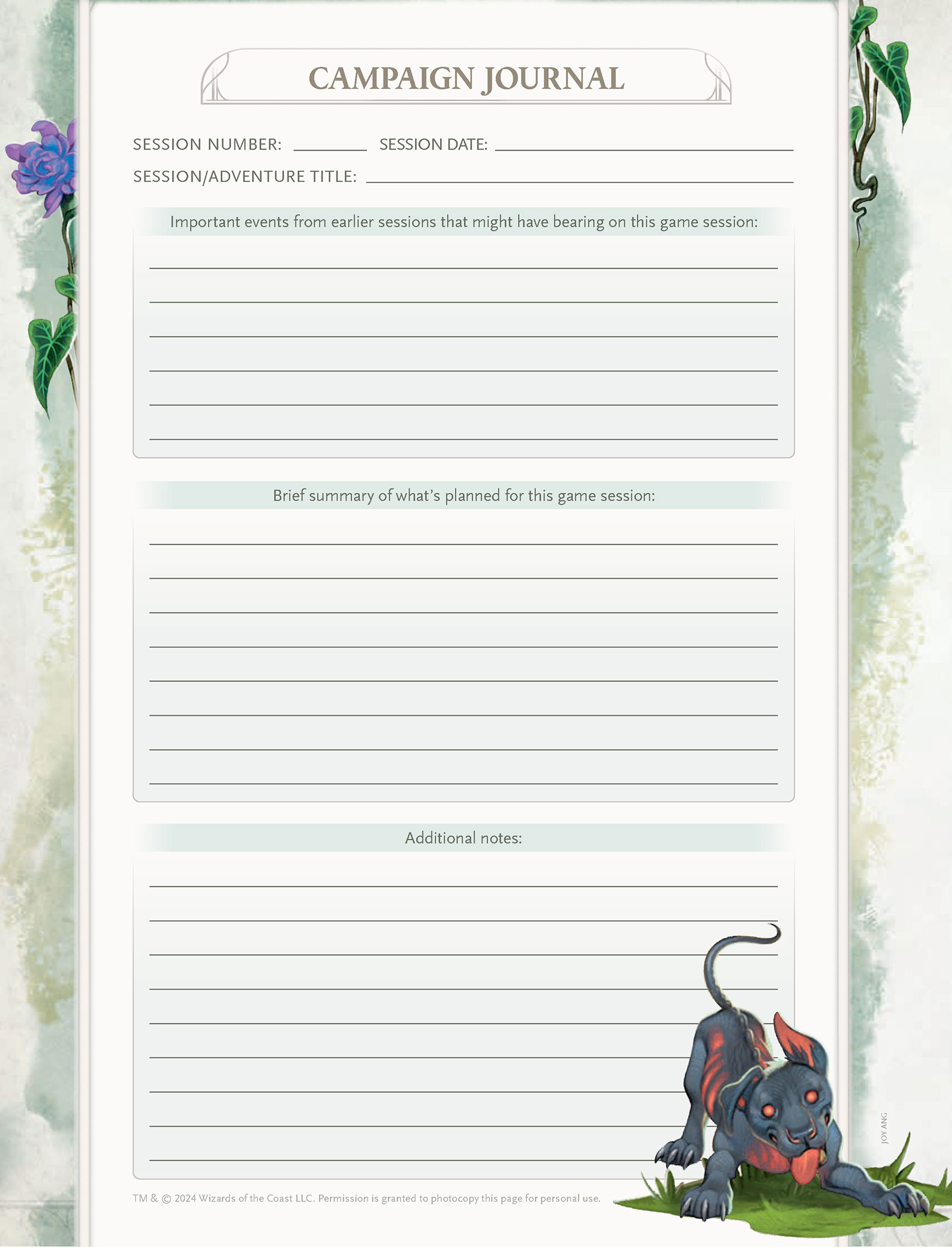

A sample Campaign Journal page is provided. Make copies of it, or use it as inspiration for your own journal pages.

Using Your Journal

Use your journal to plan out your next game session (see “Preparing a Session” in chapter 1). Then, when the game session is over, use the journal to capture anything else of importance that might have bearing on future sessions, such as the name of an NPC you created on the fly or a critical piece of information the characters learned.

During a game session, you can use your campaign journal to quickly recall a piece of information you’ve forgotten (such as the name of a character’s mule) or to jot down things you want to remember later (such as the name of a tavern). In this way, the journal becomes a living chronicle of the campaign in flight.

Foreshadowing

Foreshadowing is a storytelling technique that never goes out of style. Players love it when something happens in a game session that hearkens to some event from an earlier session.

Foreshadowing is about planting seeds early so you can reap the rewards later. Having an up-to-date campaign journal makes foreshadowing easier because you can reread your notes from earlier game sessions and identify things that could resurface in upcoming sessions, giving past events greater weight or a bigger payoff. Consider the following example.

The characters find the dead body of an unidentified halfling adventurer. A search of the body yields a cameo necklace containing the portrait of another halfling. A character decides to keep the cameo, which was intended as a bit of embellishment. You make a note of it in your journal. Months later, while planning a future session, you flip through the journal and are reminded of the cameo. It inspires you to plan a chance encounter with another halfling, whom the characters might recognize as the one depicted in the cameo. What happens if the characters return the cameo to this halfling? This halfling could be tied to a bigger plot or have information that could help the characters resolve some conflict. Suddenly, a minor trinket foreshadows bigger events to come.

Adventure Stockpile

Besides tracking each session of your campaign, keep a list of adventure ideas. Even if you don’t end up using every adventure idea, having a stockpile will keep you ready for whatever your players throw at you, and you can even borrow pieces of various ideas to incorporate into future adventures. Not every adventure needs to build on earlier plots; a good stand-alone adventure tucked in the middle of a serialized campaign can be a welcome change of pace for you and your players.

Campaign Premise

Everything outlined about the story of an adventure in chapter 4 is true of a campaign’s story as well: a campaign is like a series of comics or TV shows, where each adventure (like an issue of a comic or a TV episode) tells a self-contained story that contributes to the larger story. Just like with an adventure, a campaign’s story isn’t predetermined, because the actions of the players’ characters will influence how the story plays out.

Campaign Characters

The characters are the focus of every D&D adventure, and their players are your partners in developing their characters’ epic journeys.

By working with your players to understand what excites them most, you can craft stories they want to see their characters star in. You can also more effectively draw players into adventure plots (see “Draw In the Players” in chapter 4) if you understand what motivates both them and their characters.

Player Input

It’s not up to you to create every aspect of a D&D campaign. Players contribute through their characters’ actions and by directly sharing what they want to see in a campaign. You can learn about your players’ preferences in two ways:

Direct Input. Ask your players what they want to do in a campaign. Regularly inquire about how they think the campaign is going, what they’d like to experience more of, and what elements they’d like to explore further. After a session concludes and between sessions are great times to ask players for thoughts about the campaign.

Indirect Input. The choices a player makes, starting at character creation, can indicate what they want to see in the game. For example, a Rogue player likely wants opportunities for subtlety or skulduggery, while a Barbarian player likely craves combat. Take note of what encounters players are enthusiastic about, and seek ways to help the players’ characters shine.

Character Arcs

Like most protagonists in film and literature, D&D adventurers face challenges and change through the experience of overcoming them. By incorporating each character’s motivations into your adventures and setting higher stakes through play, you’ll help characters grow in exciting ways. You can use the DM’s Character Tracker sheet to keep track of key information about each character. See “Getting Players Invested” in this chapter for more ideas.

Character Motivations. For each character, think about what motivates them to adventure. Motivations generally fall into the following categories:

Goal. A character’s goal is a short-term reason for the character to adventure. At the start of a campaign, this might be a desire for treasure, a thirst for excitement, or some need from a character’s backstory. As characters continue to adventure, they’ll find different goals to pursue, such as finding a lost relic, honoring an ancestor, avenging a fallen mentor, or defeating a villain.

Ambition. A character’s ambition is a broad, personal aspiration the character hopes to achieve through a lifetime of adventuring. A character might dream of becoming a legendary knight or bringing peace to their homeland. Ambitions might be unrelated to the character’s current goal.

Quirks and Whims. Quirks and whims are a character’s preferences, impulses, or other traits. They often emerge during play, such as a character’s tendency to one-up a rude innkeeper or their oft-expressed fondness for displacer beast fur.

Players often reveal their characters’ motivations through play. If you’re uncertain or a character’s motivations seem to have changed, it’s OK to ask players for clarification.

Family, Friends, and Foes. A character’s origin (species and background) implies some amount of backstory, suggesting the character’s family and what the character did before becoming an adventurer. Take note of specific background characters—friends, foes, family members, and others—who might appear in the campaign.

Should these background characters become important to the campaign, work with the player to develop them in detail. Revealing a character’s lost sibling or childhood rival midcampaign should be handled carefully to avoid straining credulity. Make sure a player is comfortable with new developments about their character before introducing them.

Character-Focused Adventures. Adventures should occasionally highlight character motivations or elements of their backstory. Here are a few examples of character-focused adventures:

- A rival from a character’s past shows up to settle a grudge.

- A sneaky character puts their skills to the test by leading the rest of the party to conduct a heist.

- A character learns the location of a magic item needed to save their hometown.

- A spellcasting character must undertake a trial to join an exclusive group of spellcasters.

Any adventure that focuses on a single character should incentivize the whole party to participate—even if just to help their companion. Avoid focusing adventures on one character too often, and look for opportunities to have character-focused adventures for each character from time to time.

Setting New Goals. Characters can change their goals whenever they please, but you can encourage them to do so by giving them significant victories roughly every 5 levels. When characters accomplish their goals, consider the following questions:

- How does completing this goal create a new challenge?

- How is this victory only part of what the character wants to achieve?

- Who might be upset by the character completing this goal?

- What is a reward the character will be excited to receive that also moves them closer to their ambition?

Use the answers to these questions to develop new character goals and to inspire further adventures.

Building on the Characters’ Actions. Sometimes it can be fun to let the players steer the campaign by having their characters’ actions dictate future adventures. For example, if the characters buy a tavern using the treasure they’ve amassed, you can adjust the campaign so that the tavern has a role in future adventures. One adventure might involve a competitor trying to put the characters’ tavern out of business. Another might use the tavern as the setting for a murder mystery.

Campaign Conflicts

One way to ensure your campaign’s longevity is to come up with three compelling conflicts you can create adventures around. Introduce these conflicts early in the campaign. As the campaign unfolds, focus adventures on different conflicts to keep the players’ excitement high.

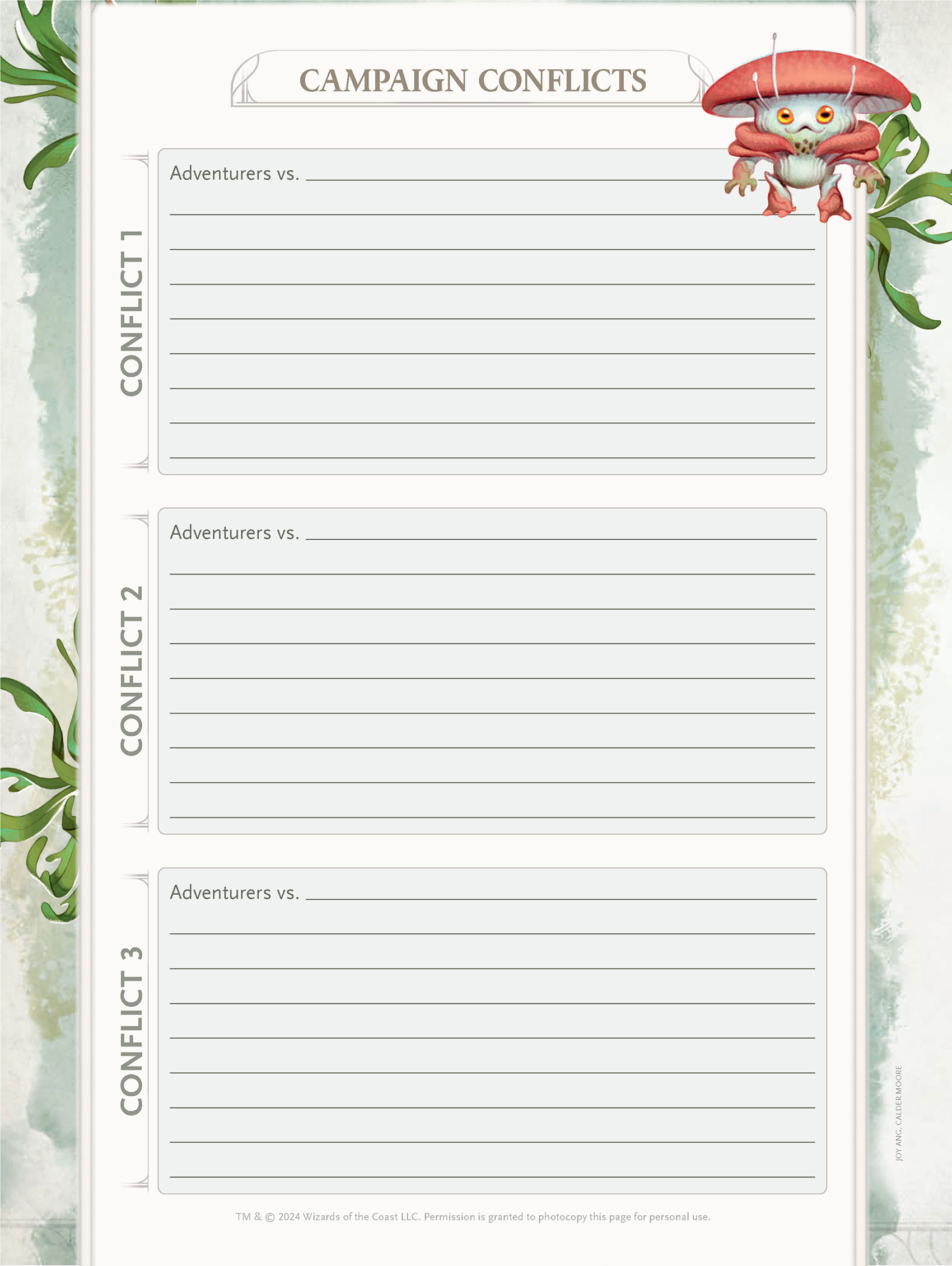

Use the Campaign Conflicts tracking sheet to record your campaign’s conflicts (with room to add details or notes). A conflict can be as big or as small as you like, and it’s nice to have at least one conflict that can be resolved quickly. Each conflict should involve the adventurers against some antagonistic force, though you can also create conflicts between two powerful forces without necessarily knowing which force (if either) the adventurers will align themselves with. The “Flavors of Fantasy” section below provides examples of conflicts that reinforce particular themes.

If a conflict reaches a satisfying end before the end of the campaign, create a new conflict to replace it. You can also replace conflicts that don’t resonate with your players as well as conflicts you’re having trouble building adventures around.

Conflict Arcs

In the same way you think about character arcs over the course of a campaign, think about how each conflict might manifest over the course of the campaign. How do the characters first encounter the conflict? How does the conflict develop over time? What might a climactic ending to that conflict look like?

One helpful way to structure a conflict arc is to use the tiers of play described in chapter 4. Levels 5, 11, and 17 represent milestones in character power and capabilities, and they can also be story milestones in the arc of your campaign. The shift from one tier to another is an ideal time to wrap up a campaign conflict and introduce a new one that has a broader reach and represents a greater threat. The threshold of a new tier can also be an opportunity for characters to realize the scale of a conflict they’ve been dealing with—to realize, for example, that the bandits they fought throughout their first four levels are merely puppets of an enemy nation they must confront in the second tier.

The “Greyhawk” section in this chapter has examples of conflict arcs.

Flavors of Fantasy

Your D&D campaign might be inspired by a particular flavor of fantasy, several of which are discussed in the sections that follow. Any of these fantastical subgenres can be informed and inspired by the cultures, myths, legends, and fantasies of any culture: an epic fantasy campaign could draw on French romances or Chinese wuxia stories, a mythic fantasy campaign could be based on Greek myth or the Epic of Gilgamesh, and so on.

Heroic Fantasy

Heroic fantasy features adventurers bringing magic to bear against monstrous threats—the default subgenre presented in the core D&D rulebooks.

Heroic Fantasy Conflicts. Heroic fantasy campaigns often revolve around delving into ancient dungeons in search of treasure or to destroy monsters or villains. Consider conflicts like these to drive the action of a campaign:

Evil Cult. Wicked cultists infiltrate a peaceful realm to free an ancient evil entity trapped in a dungeon. Releasing the entity would surely spell the realm’s doom.

Fungal Plague. To protect a primeval forest from the encroachment of hunters and settlers, druids unleash a fungal plague that quickly gets out of hand.

Old Enemy. An elusive villain who plagued the characters years ago resurfaces, giving the characters a chance to finally bring the villain to justice.

Sword and Sorcery

A sword-and-sorcery campaign features a grim world of evil spellcasters and decadent cities, where the protagonists are often motivated more by greed and self-interest than by altruistic virtue.

Sword-and-Sorcery Conflicts. In this flavor of campaign, magic-users often symbolize the decadence and corruption of civilization, and mages are the classic villains of these settings. Magic items are therefore rare and often dangerous. Consider conflicts like these to drive the campaign:

Evil Adventurers. An evil band of experienced adventurers wields power and influence to oppress hapless folk.

Evil Weapon. A knight under the influence of a sentient, evil weapon terrorizes a peaceful realm. Cultists worship and protect this weapon, which must be seized and destroyed to end the threat.

Forgotten Dynasty. The long-lost seat of a forgotten dynasty rises from the sea or the desert sands, and its people launch a campaign of conquest.

Epic Fantasy

An epic fantasy campaign emphasizes the conflict between good and evil, with the adventurers on the side of good. These heroic characters are driven by a higher purpose than selfish gain or ambition. Characters might struggle with moral quandaries, fighting the evil tendencies within themselves as well as the evil that threatens the world. And the stories of these campaigns often include an element of romance: tragic affairs between star-crossed lovers, passion that transcends even death, and chaste adoration between knights and nobles.

Fortresses on the backs of dragon turtles rise from

the depths, heralding the return of a long-lost dynasty

Epic Fantasy Conflicts. Conflicts like these highlight the themes of an epic fantasy campaign:

Apocalypse. A prophecy predicts the end of the world unless the adventurers intervene. Apocalypse cultists oppose the characters at every turn.

Dragon Tyrant. An evil and powerful dragon moves into the region, upsetting the ecology and demanding tribute from nearby settlements.

The Foe Time Forgot. An evil foe believed long dead emerges from the Feywild, alive and well after being lost in time. This foe seeks revenge against the descendants of long-dead enemies.

Mythic Fantasy

A mythic fantasy campaign draws on the themes and stories of ancient myth and legend, from Gilgamesh to Cú Chulainn. Adventurers attempt mighty feats of legend, aided or hindered by the gods or their agents—and the characters might have divine ancestry themselves. The monsters and villains they face might have a similar origin. The chimera in the dungeon isn’t just a random beast but the product of a divine curse.

Mythic Fantasy Conflicts. Conflicts like these highlight the themes of a mythic fantasy campaign:

Divine Trials. Seeking a gift or favor from the gods, the adventurers undertake a series of trials that lead them to the realms of the gods, where the adventurers can plead their case.

Divine Wrath. After a temple is sacked, a vengeful god sends an escalating series of woes upon a kingdom until the temple’s relics are returned.

Giants. An enormous castle on a cloud settles over the land. The characters can battle the giants living there or try to broker a lasting peace.

Supernatural Horror

If you want to put a horror spin on your campaign, the Monster Manual is full of creatures that suit a storyline of supernatural horror. An essential element of such a campaign is an atmosphere of dread, created through careful pacing and evocative description. Your players contribute too; they must be willing to embrace the mood.

Whether you want to run a full-fledged horror campaign or a single creepy adventure, discuss your plans with the players ahead of time. Horror can be intense and personal, and not everyone is comfortable with such a game. (The advice on discussing limits under “Ensuring Fun for All” in chapter 1 is particularly important for a horror game.)

Supernatural Horror Conflicts. A supernatural horror campaign often features Undead or demonic foes whose evil transcends the merely mortal. Consider conflicts like these to drive the campaign:

The Faceless Lord. Juiblex, the Faceless Lord, oozes out of the Abyss and into the Underdark. The characters hear from subterranean folk who need help defeating the demon lord and its minions.

School of Necromancy. Vampires open a college of necromancy, attracting evil necromancers who need fresh corpses for their studies. An order of vampire hunters seeks the characters’ help.

Undying Monarch. A venerable monarch clings to power by worshiping Orcus and becoming a lich.

Intrigue

Political intrigue, espionage, sabotage, and similar cloak-and-dagger activities can provide the basis for an exciting campaign. In this kind of game, the characters might care more about skill proficiencies and making friends in high places than about attack spells and magic weapons. Social interaction takes on greater importance than combat. Make sure your players know ahead of time that you want to run this kind of campaign. Otherwise, a player might create a combat-focused character, only to feel out of place among diplomats and spies.

Intrigue Conflicts. Conflicts like these are ripe for an intrigue campaign:

Feuding Fiefs. Two fiefs or settlements have been feuding for years. The characters are drawn into the ongoing feud after helping one side.

Royal Rivals. The sudden death of a sovereign plunges a kingdom into chaos when the rightful heir is challenged and threatened by rivals.

Scheming Adviser. After a monarch takes an interest in the characters, they become targets of the monarch’s most trusted adviser, who is scheming to become the true power in the realm.

Mystery

A mystery-themed campaign puts the characters in the role of investigators, perhaps traveling from town to town to crack tough cases that local authorities can’t handle. Such a campaign emphasizes puzzles and problem-solving in addition to combat prowess. An adventure composed of nothing but puzzles can become frustrating, so be sure to mix up the kinds of encounters you present.

Mystery Conflicts. A mystery might set the stage for the whole campaign. The characters might uncover clues to this mystery from time to time, while individual adventures might be only tangentially related to it. Consider conflicts like these for a mystery campaign:

Criminal Syndicate. A many-headed criminal syndicate seeks economic and political power. The syndicate has spies everywhere, including among the adventurers’ families or friends.

Shape-Shifting Assassins. A secret association of doppelgangers or other shape-shifters slowly assassinates prominent figures one by one.

To Catch a Thief. An extraordinary thief steals only the most valuable jewelry and works of art. The characters might become a target of the thief when they acquire a priceless treasure.

The bold adventurer Murlynd has

visited many worlds and has a fondness

for six-shooters and talking clocks

Swashbuckling

The swashbuckling adventures of pirates and musketeers make for a dynamic campaign in which dashing, charming heroes weave their way through palace intrigues and leap from balconies onto waiting horses to escape dogged pursuers. In a swashbuckling campaign, the characters typically spend a lot of time in cities, in royal courts, and aboard seafaring vessels. Nevertheless, the heroes might end up in classic dungeon situations, such as escaping from a prison cell block or searching storm sewers to find a villain’s hidden chambers.

Swashbuckling Conflicts. Conflicts like these highlight the themes of a swashbuckling campaign:

Inherited Antagonists. A character inherits a magic item from a deceased relative, unaware that this relative’s enemies are after the item.

Pirates and Privateers. A new monarch cracks down on piracy by commissioning privateers and naval officers to hunt pirate ships.

The Waking Deep. A monstrous horror slumbering in the depths of the ocean stirs, driving minions such as sahuagin, merrows, or dragon turtles to attack seafaring vessels.

War

A campaign focused on warfare centers on heroes whose actions turn the tide of battle. The characters carry out specific missions: capture a magical standard that empowers undead armies, gather reinforcements to break a siege, or cut through the enemy’s flank to reach a demonic commander. The party might also support the larger army by holding a strategic location until reinforcements arrive, killing enemy scouts, or cutting off supply lines. Information-gathering and diplomatic missions can supplement combat-oriented adventures.

War Conflicts. Conflicts like these highlight the themes and flavor of a war campaign:

Freedom Fighters. Poorly armed and disorganized subjects of a tyrant revolt.

Invaders. A militaristic nation invades its benevolent neighbors.

Pawns in a Game. A war rages on for decades, its original cause all but forgotten. The people caught up in it strive to find meaning and purpose in a bleak and violent world.

Crossing the Streams

Deep in D&D’s roots are elements of science fiction and science fantasy as well as a wide-ranging collection of fantasy inspiration, and your campaign might draw on those sources as well. You can send your characters hurtling through a magic mirror to Lewis Carroll’s Wonderland, put them aboard a ship traveling between the stars, or set your campaign in a far-future world where laser weapons (see “Firearms and Explosives” in chapter 3) and Wands of Magic Missile exist side by side.

Crossing the Streams Conflicts. Conflicts like these create opportunities for crossing the streams:

Beyond the Magic Mirror. A mysterious mirror in a strange dungeon is a portal into a different world where whimsical tales unfold—or perhaps some version of the modern world.

Gamma World. The characters inhabit a post-apocalyptic wasteland that is largely medieval in feel, but isolated outposts still hold futuristic technology from before the cataclysm.

Invaders from Wildspace. Spaceships land on the characters’ world and disgorge hostile creatures armed with advanced technology.

Campaign Setting

Just like an adventure’s setting (as described in chapter 4), a campaign setting is an essential part of a campaign’s premise, shaping the kinds of stories that unfold there.

As the DM, you have two options when choosing a campaign setting:

- Use a published campaign setting.

- Create your own campaign setting.

Whether you create your own campaign setting or use a published one, the world of your game is always your own. You can customize it to suit your tastes and those of your players.

Using a Published Setting

One advantage of using a published campaign setting is that much of the world-building is done for you. However, this means your players might know as much about the setting as you do. You can get around this by changing key aspects of the setting to better serve your needs, which has the added benefit of challenging your players’ expectations.

The D&D Settings table describes several established campaign settings.

D&D Settings

| Setting | Description |

|---|---|

| Dark Sun | Heroes make their mark on a postapocalyptic world defiled by magic and forsaken by the gods. |

| Dragonlance | The forces of good battle the evil queen of dragons and her armies in the world-shaking War of the Lance. |

| Eberron | In the aftermath of a deadly war, magically advanced nations rebuild as a cold war threatens lasting peace. |

| Exandria | Heroes make names for themselves in the world made popular by the streaming show Critical Role. |

| Forgotten Realms | Larger-than-life heroes and villains struggle to determine the fate of the world as they explore the ruins and dungeons of fallen kingdoms and long-forgotten empires. |

| Greyhawk | As tensions rise among warring nations, heroes plunder dungeons to gain the magic and might they need to defeat the growing forces of evil. |

| Planescape | Sigil, the City of Doors, is where heroes begin to explore the wonders of the D&D multiverse and its many planes of existence. |

| Ravenloft | Heroes are drawn into the gloomy Domains of Dread—cursed realms ruled by evil lords—and must find a means of escape. |

| Ravnica* | In a world-spanning city, ten disparate factions draw heroes into a web of adventure and danger. |

| Spelljammer | Travel among the stars on a spelljamming ship, and visit worlds floating in the majestic oceans of Wildspace. |

| Strixhaven* | Strixhaven, a school of magic, serves as a hub of learning and adventure. |

| Theros* | Heroic destinies wait to be fulfilled in this setting inspired by the myths of ancient Greece. |

| *This setting is based on a Magic: The Gathering world. |

Creating Your Own Setting

One advantage of creating your own world is it can be whatever you want it to be. Your players will never know more about the world than you do, which can be both a comfort to you and a source of wonder to your players. Moreover, you don’t need to memorize any source material about the campaign setting, other than what you create for yourself.

Whether you create a setting from scratch or borrow elements from established settings, the result needs to resonate with your players. As you create your world, ask your players what settings and genres they enjoy, then use those sources for inspiration to create compelling locations, memorable inhabitants, exciting conflicts, and an internal logic that will resonate with your players.

Five Questions to Consider. As you contemplate a new campaign setting, think about your answers to the following questions:

What’s Your Campaign Setting Called? Choose an evocative name for your setting. It can be a word or phrase that reflects the theme and tone of the game, or just a made-up name that sounds cool to you. Keep a running list of ideas as you decide on other aspects of your setting.

What Factions and Organizations Are Prominent? Nations, temples, guilds, orders, secret societies, and colleges shape the social fabric of the setting. What organizations or societal groups play an important part in your setting? Which ones might be involved in the lives of player characters as patrons, allies, or enemies? What organizations can characters join, becoming part of something larger than themselves?

How Common Is Magic? Spellcasters and magic item shops might be common, rare, or practically nonexistent in your world. How readily available are spells such as Lesser Restoration, Raise Dead, and Teleportation Circle? Is magic so widespread that it’s part of daily life, or so rare that it conjures all sorts of superstitions?

What Mysteries Does the World Hold? Every campaign setting has mysteries: a fabled land across the sea, a grim forest hiding a terrible secret, restless spirits haunting a ruined keep for reasons unknown, an ancient dungeon built for a forgotten purpose, and so on. Dream up as many mysteries as you wish—you never know which ones will seize your players’ imaginations and become central to the campaign—and record them in your campaign journal.

What Roles, If Any, Do the Gods Play? What greater gods, lesser gods, and quasi-deities are present or worshiped in your world? If there are gods, how involved are they in the world? Are they distant and detached beings, or do they appear before their worshipers and meddle in mortal affairs?

Campaign Start

With your campaign journal in hand and the basic premise of your campaign (characters, conflicts, and setting) in mind, it’s time to consider how to begin the campaign.

Session Zero

At the start of a campaign, you and your players can run a special session—called session zero because it comes before the first session of play—to establish expectations, share ideas, and discuss house rules, with the goal of ensuring the game is a fun experience for everyone involved. The “Ensuring Fun for All” section in chapter 1 covers some of the most important groundwork you need to establish at the start of a new campaign.

Often session zero includes building characters together. As the DM, you can help players during character creation by advising them on which options best suit the campaign.

Character Creation

When players are choosing their characters’ classes and origins, you can restrict options that are unsuitable for the campaign.

Encourage the players to choose different classes so that the adventuring party has a range of abilities. It’s less important that the party include multiple backgrounds or species; sometimes it’s fun to play an all-Dwarf party or a troupe of adventuring Entertainers.

The origins the players choose define who their characters were before becoming adventurers. Think about how the characters’ backgrounds might inform adventures in your campaign. For example, if a player chooses the Criminal background, help the player flesh out their character’s criminal past, and use that information when building relevant storylines into the larger campaign.

Starting Level. What level are the characters when they start? Many D&D campaigns start the characters at level 1. If you want the characters to be a bit more resilient and your players are experienced, start the campaign at level 3 instead. (See the Player’s Handbook for rules on starting at higher levels.)

Bringing the Party Together

During session zero, help the players come up with explanations for how their characters know each other and have some sort of history together, however brief that history might be. To get a sense of the party’s relationships, here are some questions you can ask the players as they create characters:

- Are any of the characters related to each other?

- What keeps the characters together as a party?

- What does each character like most about each member of the party?

- Does the group have a patron—an individual or organization that points them toward their adventures?

If the players are having trouble coming up with a story for how their characters met, you can suggest the following options.

Bonding Event. Some bonding event (such as a wedding, a festival, or a funeral) brings the characters together, whereupon they quickly discover a shared sense of purpose.

Happenstance. Someone puts out a call for adventurers to complete a quest, and the characters answer the call. Alternatively, all the characters could meet by accident, only to discover they’re headed to the same place, or they could find themselves trapped together.

Mutual Acquaintance. The characters are introduced to one another by a mutual NPC acquaintance whom they all trust. This shared acquaintance could serve as a patron for the party—perhaps a representative of an organization (an academy, a criminal syndicate, a guild, a military force, or a religious order), a politically powerful person (an aristocrat or even a sovereign), or a magical creature like a sphinx or a dragon.

Shared History. The characters grew up in the same place and have known one another for years. Despite their different backgrounds and training, they’re already good friends.

Tavern Gathering. The characters meet in a tavern over mugs of ale and decide to embark on a life of adventure together—a tried and true trope!

Setting the Stage

Session zero is a great time to share basic information about the campaign with your players. Such information typically includes the following:

Starting Location Details. Your players need basic information about the place where the characters are starting, such as the name of the settlement, important locations in and around it, and prominent NPCs they’d know about (see “Starting Location”).

Key Events. Describe any current or past events that help frame the campaign. For example, the campaign might start on the heels of a great war or on the day of a festival. Describing key events helps set the mood and prepare players for upcoming adventures.

House Rules. If you’re using any house rules (as discussed in chapter 1), or adopting any of the variant rules presented in this or any other book, let your players know about them.

Remember, you’ll always know more about your campaign world than the players do. Having spent all their lives in this world, though, the characters also know more than their players do. Fill in the basics of what the characters should know anytime that information matters to their adventures.

Starting Location

Begin your campaign in a location you can detail, such as a village, a neighborhood in a larger city, an outpost, or a roadside tavern. Be prepared to give players enough information about that location to help them figure out what ties, if any, their characters have to it. Once you have this campaign hub fleshed out, create one or two local attractions that might serve as adventure locations, such as a haunted house on the outskirts of town or a dungeon complex tucked in the nearby hills.

A time of sorrow can bring people together and even launch an adventuring party

If you’re using a published campaign setting, pick any location in that setting and develop it as you like. A published setting or adventure might give you all the details you need. The Free City of Greyhawk, described later in this chapter, is an ideal starting location and illustrates the kinds of things to consider as you detail a starting location.

If you’re building your own setting, start small by detailing only this starting area. The rest of your setting can remain undeveloped for now. Don’t spend too much time fleshing out the geopolitical landscape of your world or locations the adventurers aren’t likely to visit right away; save those fun tasks for when you and your players have a better sense of where the campaign is headed.

First Adventure

If you’re using a published adventure to launch your campaign, use the character hooks in that adventure to bring the characters from their starting location to the adventure’s action. Many campaigns begin with a published adventure and then develop organically as the characters explore beyond the scope of the adventure.

If you’re creating your own adventure for the start of your campaign, refer to the advice in chapter 4. Keep the first adventure relatively short and simple, allowing plenty of time for the characters to get to know each other as the players roleplay. What’s most important is that they begin to feel like an adventuring party and get comfortable with their abilities. The full scope of the campaign can unfold to them later.

Plan Adventures

A D&D campaign is like a garden. Each new adventure plants new seeds in the garden, which requires regular tending lest it run wild. Over time, your campaign will grow and flourish in ways you expected and in ways that will surprise you. You might need to weed out elements that aren’t resonating with your players while planting new elements to tantalize them.

Most D&D campaigns grow organically, rather than having all their elements set in stone from the get-go. From time to time, the characters’ decisions will require you to improvise and create new campaign elements on the fly. For example, a new location might need to be developed to address the needs of the unfolding story, or certain NPCs might need fleshing out at a moment’s notice. Other parts of this book, such as the “Nonplayer Characters” and “Settlements” sections in chapter 3, can help you expand your campaign quickly.

Episodes and Serials

There are two basic ways to think about how adventures fit together in your campaign: as distinct episodes or as a serialized story. If you’re not sure which type of campaign to run, ask your players what they prefer. If your players have different preferences, you can intersperse episodic, stand-alone adventures among serialized adventures to break up the bigger story.

Episodes

An episodic campaign is a campaign in which the component adventures don’t combine to form an overarching story. Episodic adventures are stand-alone quests, and the villains who appear in one adventure rarely resurface to trouble the characters again. If your game group plays infrequently, an episodic campaign might be ideal because the players can enjoy the current adventure even if they’ve forgotten the details of earlier adventures.

Starting a New Episode. In an episodic campaign, the start of a new adventure doesn’t necessarily have any connection to the end of the last one. The action might pick up immediately after the end of the previous adventure, but it might instead begin weeks, months, or years after the last adventure, allowing interim events to unfold while the characters take a break from adventuring.

Serials

A serialized campaign is one continuous story broken up into smaller parts that flow naturally from one to the next. It often has one or more overarching threats, and the outcome of one adventure can affect how the rest of the campaign unfolds. If your game group meets regularly and often, a serialized campaign allows you to keep your players guessing what will come next as the campaign builds toward a satisfying conclusion.

Linking Adventures. In a serialized campaign, make connections between the end of one adventure and the start of the next to help it feel like a connected story. Sometimes you can simply continue the current storyline with new locations to explore and new threats to overcome. Alternatively, you can use the Adventure Connections table to inspire a link from one adventure to the next. The table suggests things you can do near the end of one adventure to lead characters into the next one.

Adventure Connections

| 1d6 | Adventure Connection |

|---|---|

| 1 | Introduce a person, an object, or information that the characters need to transport safely to a location involved in the new adventure. |

| 2 | Have a major villain flee to a location that features in the new adventure. The characters might be able to pursue the villain, or they might have to search for clues about where the villain has gone. |

| 3 | Introduce clues suggesting that a villain or another NPC in this adventure is part of a larger group—a group that features prominently in the new adventure. |

| 4 | Introduce a villainous group that’s featured in the new adventure by having its agents spy on or interfere with the characters’ activities. |

| 5 | Have travelers bring news of events transpiring elsewhere, leading characters toward the new adventure. |

| 6 | Give the characters a treasure that’s wrapped in mystery they’ll need to unravel in the new adventure. |

Getting Players Invested

To get your players excited about and invested in your campaign, create a setting that features people and places they recognize and where their characters’ choices matter.

The following sections suggest ways to help you create a world your players will be excited to explore.

Recurring Elements

When characters form relationships—friendships, business arrangements, or even lasting antagonism—with the people and places of your setting, those people and places stick in the players’ minds. Introduce opportunities to forge these lasting relationships early and often.

Consider featuring recurring elements such as these in your game:

Community. Introduce a small group or community the characters can think of as their people, like a village, neighborhood, guild, or crew.

Home Base. Give the characters a place to call home, such as a tavern, a hideout, or a ship. Bastions, as presented in chapter 8, are ideal home bases for characters.

Prominent Friend. Create a supportive NPC whom the characters can trust and turn to when they need help, such as a local leader, an innkeeper, a patron, a retired adventurer, or a family member.

Friendly Resources. Provide experts or institutions that can assist the characters, like a temple that can provide healing or a learned sage who can help solve mysteries.

Likable Villain. Craft a villain who has at least one likable or redeeming quality the characters can appreciate—ideally a villain who isn’t preoccupied with killing or harming the characters.

As your campaign continues, introduce new people and locations, and bring back favorites from earlier in the campaign for the occasional cameo.

Player Favorites

It’s often easier to describe people and places that are hostile or frightening than it is to detail a feature you want characters to love. How can you know what rustic scene will make a character associate a place with home or what personality quirk will remind a character of their favorite mentor? You can ask a character’s player directly, but instead consider handing over your narrative reins and letting a player describe the perfect detail.

For example, say you have a peaceful village you plan to feature across several adventures. You hope the characters will connect with the place and treat it as home. As the characters enter the community, they smell something amazing. At this point, you could describe something you think smells good or something you think a character would like. Or you can ask a player, “The smell of something amazing drifts from around the corner. What is it?” Whatever the player’s answer—cinnamon rolls from a nearby baker, firework charges being prepared for a celebration, or anything else—becomes part of the village, and the player has added an important detail to the location.

You can use player input whenever you want to pinpoint something meaningful to the characters and their players. Consider asking players questions like these whenever you want to describe something in an impactful way:

- The tavern owner brings out your favorite dish—cooked to perfection. What’s the dish, and what makes this one remarkable?

- The curio shop is selling a trinket that reminds you of one of your family members. What’s the trinket, and who does it remind you of?

- The local children are playing a game you played in your hometown. What is it?

- The young pickpocket reminds you of someone you once knew. Who?

- From the animate mass of murderous dolls scrambles a figure that reminds you of your favorite childhood toy. What is it?

Questions such as these don’t need to draw on warm memories. Having players describe what unsettles or disgusts their characters can make menacing encounters more impactful as well. In any case, take note of interesting character details that your players share, and record them in your campaign journal, as these details might be useful inspiration for later adventures.

In the Dragonlance setting, Tanis and Tika call their local

inn home: a place to see familiar faces like Fizban the Fabulous

Acknowledge the Incredible

Adventurers are, by their nature, remarkable. Even at level 1, they perform miraculous deeds and possess qualities that set them apart from common folk. Reinforce this in your game. NPCs don’t need to gush over the characters, but the characters’ reputations as heroes, problem-solvers, or wonderworkers should be cemented early and develop throughout a campaign.

During every session, look for opportunities to make the characters feel like the stars of the story, and try to answer one or more of the following questions:

- How are the characters the perfect people to solve a problem?

- How are the characters’ talents highlighted during the adventure?

- What stories do NPCs know of the characters’ past exploits?

- How might an NPC comment on a character’s abilities or recognize that they’re special?

Break Episodes

It’s easy to get caught up in a story with dramatic stakes, pitting characters against mounting threats. But every so often, at least once every three to five levels, give the characters a break—a low-stakes session or adventure that has nothing to do with the overarching plot or broader perils.

A break episode can be an opportunity for the characters to reflect on the events of the ongoing campaign, explore the nuances of the world, and further develop the relationships between them in a more relaxed setting. Give the group space to breathe, note developments you want to highlight later, then continue with your adventures.

Consider these ideas for a break episode.

Bastions Episode. The characters take a break from adventuring to tend to their Bastions (see chapter 8), with players taking one or more Bastion turns and describing what happens.

Carnival Episode. A carnival tempts the characters with magical attractions, games, and prizes. The Witchlight Carnival, described in The Wild Beyond the Witchlight, is one such carnival.

Creature Comedy. The characters encounter monsters with a comedic flavor—such as flumphs, pixies, faerie dragons, or chatty mimics—in a situation that leads to mischief and humor rather than combat.

Missing Pet Episode. Someone’s pet is missing. The characters must search a settlement and connect with locals to help find it.

Shopping Episode. A friendly NPC asks the characters to help shop for someone’s birthday.

Special Event Episode. The characters are invited to a sporting event, holiday celebration, fancy dinner, or ball.

Vacation Getaway. The characters relax on a quiet beach, enjoy the comforts of a grateful noble’s villa, withdraw to a serene monastery, or while away the hours in a fairy hot spring.

Time in the Campaign

Most conflicts in a D&D campaign take weeks or months of in-world time to resolve. A typical campaign concludes within a year of in-world time unless you allow the characters to enjoy lengthy periods of quiet time between adventures.

If you don’t want to track the passage of days, weeks, and months, you might instead track the passage of time using seasons and seasonal festivals. The answer to the question “When does this adventure take place?” can be as simple as “in the winter” or “during the fall harvest festival.”

Timed Events

Extraordinary events coinciding with certain times of year make for great adventure opportunities. Perhaps a ghostly castle appears on a certain hill on the winter solstice every year, or every thirteenth full moon is blood red and fills werewolves with a particularly strong bloodlust. The appearance of a comet in the sky might portend all manner of significant events. The festivals of the gods can serve as opportunities to launch adventures, especially if the gods themselves are involved.

Ending a Campaign

A campaign’s ending should conclude the last of the major conflicts and tie up most of the threads of its beginning and middle. (It’s OK to leave some loose ends for characters to explore in the next campaign.) You don’t have to take a campaign all the way to level 20 for it to be satisfying; wrap up the campaign whenever the story reaches its natural conclusion.

Allow time near the end of your campaign for the characters to finish up any personal goals. Their stories need to end in a satisfying way, just as the campaign story does. Ideally, some of the characters’ individual goals will be fulfilled by the final adventure. Give characters with unfinished goals a chance to finish them before the very end.

Once your campaign has ended, a new one can begin. If you intend to run a new campaign for the same group of players in the same setting, using their previous characters’ actions as the basis for legends is one way to invest your players in the new campaign. Let the new characters experience how the world has changed because of the actions or accomplishments of the previous campaign’s characters. In the end, though, the new campaign is a new story with new protagonists. They shouldn’t have to share the spotlight with the heroes of days gone by.

Ending Sooner Than Expected

Sometimes you run out of ideas for your campaign, or it gets so sidetracked that you have no idea how to bring it to a satisfying conclusion. You might just not feel excited about it anymore, or you might be so excited with ideas for a new campaign that you can’t focus on the current one. Any of these might signal the end of your campaign.

The best way forward when you want to end a campaign is to talk to your players about it. If you’re not excited about the game anymore, it’s quite possible they’re not either, and you can change or end the campaign to everyone’s satisfaction. Consider the following possibilities:

Player Input. If you’re running out of ideas for your campaign, your players might be more than happy to supply you with some. Find out what they’d like to have happen if the campaign continues. They might give you all the inspiration you need!

Switch DMs. One of your players might have so many ideas about the future of the campaign that they’re willing to take over as the DM. You can either take over that player’s character or make a new one of your own. Let go of your plans for where the story was going, and allow the new DM to have creative control.

Transport the Characters. If you or another DM wants to start up a campaign in a new setting but the players don’t want to make new characters, consider having the characters travel through a portal to a new world.

Arrange a Grand Finale. Sometimes an end to the campaign is the right answer. Look for ways to end the campaign with a bang, even if it’s earlier than you originally planned. Flip through your campaign journal to see if there are forgotten elements you can resurface for one last hurrah.